By Mark Cioc-Ortega

Concordia Cemetery opened in 1884, Evergreen in 1893. The Smelter Cemetery was supposedly established in 1882, but was not used much before the 1890s. So, where did El Pasoans bury their dead before that? The answer, it seems, is “just about anywhere they wanted to.” Back yards, empty lots, hillsides. The population was small, the desert was vast, and the laws were lax.1

Campo Santo was the closest thing El Paso had to a “boot hill.” It was located just north of the town square (today’s San Jacinto Plaza), near the intersection of Franklin Avenue and Santa Fe Street. Campo Santo is Spanish for “saint’s field” or “blessed field,” but since April 2014 El Pasoans have been calling it “right field”: the old cemetery site now forms the southeastern corner of the city’s new Triple-A baseball stadium, Southwest University Park.

No one really knows when Campo Santo was established. It may have existed when the future El Paso was part of the Ponce Ranch and belonged to Mexico. More likely, American immigrants established it after the U.S.- Mexico War (1846-1848) to serve the new town of Franklin (El Paso). “The graveyard was convenient,” El Paso pioneer W. W. Mills recalled, “being on one of the hills on what is now known as ‘Sunset Heights.’ At one time there were more people buried there who had died by violence than from all other causes.”2 The most prominent headstone belonged to a Dr. Giddings, probably a brother or other relative of George Henry Giddings, who operated the San Antonio-Santa Fe Mail Line during much of the 1850s.

Campo Santo was not El Paso’s only early burial ground. A make-shift cemetery popped up during the Civil War on the west side of El Paso Street, near the intersection with Overland Street. A brigade of Texas Mounted Volunteers, under the command of Brigadier General Henry H. Sibley, passed through Fort Bliss in late 1861 en route to invade the Territory of New Mexico. When the Confederate forces retreated to El Paso in April and May 1862, they utilized the Overland Mail Station as a temporary hospital. Those who died at the hospital—about forty soldiers—were buried in the vacant lots across the street. To this day it is not known what ultimately happened to the corpses. The bodies may have been exhumed and reburied after the Civil War. Or they may have been unearthed when the lots were developed during the 1880s: both the St. Charles Hotel and the Myar Opera House were built across from the Overland Mail Station and W. W. Mills claims the cemetery was located “near where the Opera

House now stands.”3 Some of the bodies may still be there. The Sibley Trail Association, which delved into this mystery many years ago, thought it “probable that bones or artifacts still lie beneath some of the open spaces.”4

Figure 1. The Mills Plat of 1859. This close-up of the Mills Plat of 1859 shows the location of the Campo Santo in Block 28. Due to damage to the map, the “Campo” is partially rubbed out; only “Santo” can be read clearly. Just above the cemetery name is the image of a monument and the words “Dr. Giddings Monument.” Courtesy of the El Paso County Historical Society.

Figure 2. City Engineer Map. This close-up of a map by Juan Hart places the city cemetery (depicted as a rectangle) on a hillside one block east of where it is depicted on the Mills Plat. The word “cemetery” is written inside the rectangle but it is too smudged to read clearly. The map was probably drawn around 1883 and certainly before 1888, as the name El Paso del Norte is used instead of Ciudad Juárez. It is not known whether this cemetery is the original Campo Santo or another burial ground just east of the original one. Courtesy of the El Paso County Historical Society.

El Paso had a third downtown cemetery, this one for the Freemasons of El Paso Lodge No. 130. It began as a private burial spot for Nathan Webb, who died on October 16, 1866, and was buried in the back yard of his home on the northeast corner of San Antonio Street and Mesa Avenue (then called Utah Street). Webb’s widow donated the land to the local Lodge the following year for use as a Masonic cemetery (the Masons also built a two-story Lodge on a portion of the land at a later date). Moses Carson, the brother of the famous frontiersman “Kit” Carson, was the first Mason to be interred at the cemetery, on January 2, 1868. District Judge Gaylord Clarke—who was shot dead during a gunfight between B. F. Williams and Albert Fountain over a matter of political patronage—was interred there after his death on December 7, 1870. According to some accounts, Judge Charles Howard, a perpetrator and victim of the Salt War (1877-1878), was also laid to rest there, before being reinterred later in Austin.5

It is not known how many graves the Masonic cemetery contained, but probably only a handful. The Lodge was small, boasting just 31 members as late as 1881. The cemetery, moreover, did not survive long: in the 1870s, the Masons purchased a block of land (bounded by Franklin, Missouri, Mesa, and Oregon streets) just north of downtown for a new cemetery; and then in the 1880s they purchased two acres at Concordia and moved all the bodies there.6 Well, almost all. In the early 1900s, Adolf Schwartz purchased the first Mason site and built the Popular Dry Goods Store atop it. During the construction, workers unearthed a skeleton, probably the remains of poor ol’ Gaylord Clarke.7

When Fort Bliss was reestablished in 1878, the federal government set aside land for yet another cemetery, this one on two adjacent blocks east of Campo Santo; it is labeled “U.S. Cemetery Reserve” on city maps of that era.

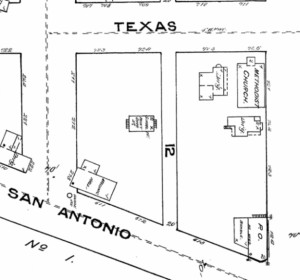

Figure 3. Sanborn Map of 1883. The Masonic Lodge No. 130 constructed a two-story building at the corner of San Antonio and Mesa Avenue (Utah Street), next to the original Masonic cemetery. The Lone Star (January 26, 1884) refers to a temporary school house “under the charge of Miss Mary Gates in a room adjoining the Masonic ceme¬tery.” This school house can be seen just north of the Masonic Lodge building, so the cemetery must have adjoined them both. Courtesy of UTEP Library Special Collections.

Shortly thereafter, however, Fort Bliss moved to Hart’s Mill, and the army established a small triangular cemetery near the parade grounds on that property. Neither the U.S. Reserve or the Hart’s Mill cemeteries were in service very long, as Fort Bliss moved again in 1893 to its current location on the La Noria mesa in northeast El Paso. The army established yet another burial site there, Fort Bliss National Cemetery, which is still in use today. The U.S. Cemetery Reserve was turned over to the city and became Buckler Square and Cleveland Square. The Buckler name disappeared when the Carnegie Public Library (forerunner to the El Paso Public Library Main Branch) was built atop the square in 1904. Cleveland Square still exists, though much of its open space disappeared when the El Paso Museum of History was built in 2007. As for the small triangular cemetery at Hart’s Mill, it fell into oblivion and is now bedecked by Interstate 10.

Yet another cemetery was established in the downtown area in 1882, this one in Mundy Heights (adjacent to Sunset Heights), most likely at or near where Mundy Park is now located. Little is known about this cemetery, except what can be gleaned from the Lone Star, one of El Paso’s earliest newspapers. According to Lone Star, the city purchased 1.5 acres from H. M. Mundy for $75. The land was approximately ¾ mile west of the Sunset Heights reservoir (which is located near the intersection of River and Randolph). And it was poorly suited for use as a cemetery. “Very serious complaints reach us regarding the new cemetery established by the city on the hill west of the water works,” wrote the Lone Star on September 9, 1882. “The soil is a loose gravel in which it is claimed that it is next to impossible to dig a decent grave. Several burials have been delayed, after the corpse and funeral procession had reached the cemetery, by the caving in of the walls of the grave and the covering up of the box provided in the bottom of the grave to receive the coffin, it being necessary to keep the mourners waiting until the grave could be cleared out.”8

It was the creation of Concordia Cemetery in 1884 that saved the downtown area from filling up with dead bodies and ill-conceived burial grounds. Today Concordia lies in the shadow of the “Spaghetti Bowl,” at the intersection of Interstate 10 and Highway 54, but it was once a working ranch about three miles east of the town. Hugh Stephenson (a Chihuahua trader and El Paso pioneer) and his wife Juana María Ascarate (the daughter of an aristocratic Mexican family) owned Concordia. During its heyday, it hosted a small settlement of immigrants and pioneers; a small Catholic Church called San Jose de Concordia el Alto; and for a short time, Fort Bliss (1868-1876). There was also a small family cemetery, which held the remains of Stephenson’s wife, Juana María, who died prematurely on February 6, 1856.

Figure 4. Fort Bliss at Hart’s Mill. This is close-up of the 1893 Fort Bliss plat shows a small triangular cemetery at the lower edge of the base. The plat is oriented eastward toward the Rio Grande. Courtesy of the El Paso County Records Office.

In the early 1880s, the descendants of Hugh and Juana Stephenson began selling off parcels of land at Concordia for use as public and private burial grounds. The City of El Paso purchased two acres for use as a pauper cemetery. El Paso County also purchased two acres for the same purpose. Six acres were set aside for public burials. Other groups—the Masons (2 acres), Odd Fellows (1 acre), Catholic Church (4 acres), the Jewish community (1 acre), the Chinese community (1/2 acre)—purchased

land there as well, and before long Concordia was a patchwork of eight adjacent cemeteries. “The old burying ground in the Satterthwaite addition [Sunset Heights] is being removed from the city limits,” the Lone Star proudly announced in 1885. “Concordia is a spot that will admit of the raising of shrubs and trees, and it will one day be the prettiest cemetery in this section if people will only co-operate to make it so.”

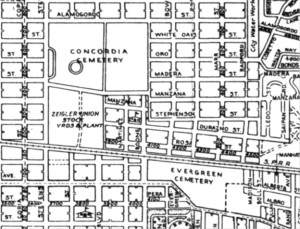

Figure 5. Map of El Paso in 1953. Concordia and Evergreen Cemeteries are remarkably close together. This sense of proximity was lost when Interstate-10 was built between them in the 1960s. Courtesy of the El Paso County Historical Society

Concordia did eventually sprout some “shrubs and trees,” though it can hardly be called the city’s “prettiest cemetery,” except for the two beautifully maintained Jewish sections. It did, however, become one of El Paso’s largest: it now sprawls across 54 acres and contains some 65,000 grave sites, including the remains of many who had originally been buried in Campo Santo and other downtown locations. Unfortunately, not all of downtown skeletons were successfully located, dug up, and reinterred at Concordia in the mid- to late 1880s: burial records were spotty; many grave markers had deteriorated or been vandalized; and the exact perimeters of the old cemeteries were unknown. So, inevitably, some graves were missed during the initial move, only to be uncovered later. In 1899, workers unearthed a skeleton while digging at Cleveland Square. “Old timers here say that the hills in this vicinity are well filled with skeletons, having been used as a cemetery for soldiers,” reported the El Paso Herald.9 In 1901, the El Paso & Southwest Railroad grading crew churned up several skeletons while working along Main Street between Chihuahua and Santa Fe streets. “The ground was formerly a cemetery,” an elderly citizen told the El Paso Herald, “known as El Campo Santo, the first man being buried in 1842, and being abandoned as a burying ground in 1862.”10 In 1908, three skeletons were dug up as gas company employees dug a trench for a pipe along Missouri Street near Mesa Avenue.11 In 1910, more skeletons were dug up in the old Camp Santo area, this time as the E. E. Neff Company excavated the foundation for a new warehouse on the intersection of Main and Chihuahua streets. The El Paso Herald reported that one of these skeletons was that of a male with boots on his feet and bullet holes in his skull, “indicating that he went over the divide by the hurry-up route.”

Figure 6. The Neff-Stiles Building on Santa Fe Street at the Corner with Mesa Street. Three skeletons in the area once known as Campo Santo were discovered in January 1910, while workers excavated the foundation for the E. E. Neff (later called the Neff-Stiles) warehouse. Courtesy of the El Paso County Historical Society.

These discoveries continued for many decades as the downtown spread and developed—each unearthed skeleton serving as a grisly reminder of El Paso’s long-buried and half-forgotten past.

Endnotes

1. This is an expanded version of an article that appeared under the same title in the online weekly Newspaper Tree (http://newspa-pertree.com/articles/2013/09/25/dead-reckon¬ing-where-were-el-pasos-earliest-cemeteries).

2. William Wallace Mills, Forty Years at El Paso, 1858-1898: Recollections of War, Politics, Adventure, Events, Narratives, Sketches, Etc. (Chicago: W.B. Conkey Co., 1901), p. 15.

3. Ibid., p. 60.

4. The Sibley Trail Association, “Confederate Burial Ground, El Paso, Texas,” unpublished manuscript (no date, but sometime after 1995), in the El Paso Vertical Files under “Ceme¬teries” at the El Paso Public Library (Main Branch).

5. John W. Denny, A Century of Freemasonry at El Paso (El Paso: Patron’s Edition, 1956), pp. 31-32 and 42-43.

6. Ibid., pp. 44, 50, and 56-57.

7. El Paso Herald (April 4, 1910).

8. Lone Star (March 29, 1882 and September 9, 1882). Quote from September 9 issue.

9. El Paso Herald (April 24, 1899).

10. El Paso Herald (August 28, 1901).

11. El Paso Times (September 2, 1908).

Figure 11. Aerial Shot of Downtown El Paso North of Main Street in 2006. Much of this area was used as burial grounds until the opening of Concordia (1884) and the relocation of Fort Bliss (1893).