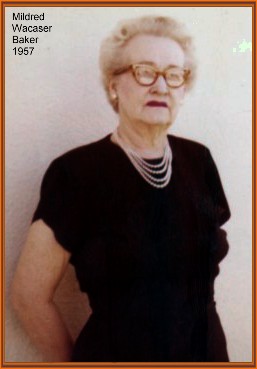

Mildred Baker: An El Paso Suffragist

Mildred Genevieve Wacaser Baker (1885-1994) was one of many El Paso women who fought for the right to vote. Baker lived to be 109, long enough to witness the first female mayor, county judge, state senator and district judge in the El Paso area. Baker was a suffrage activist: “I campaigned up and down the country trying to [get] men to give women the right to vote,” she explained in an interview with the El Paso Times. “Most of them told me if women got the vote, they’ll just end up voting the way their husbands tell them to.”[1]

Baker was born in Newton County, Missouri in the Ozark foothills. She was one of seven children born to Madison and Cynthia Wacasar. Baker married Earl Bowers and had a son, James Madison Bowers. That marriage ended in divorce. She married El Paso Traffic manager, Sheldon S. Baker, in 1916. The couple had one child, a son, Sheldon Jr. Baker would outlive both of her sons and husband. Before coming to El Paso in 1910, Baker lived in Colorado as a single mother working as a stenographer.

In 1915 she became a founding member of the El Paso Equal Franchise League, which was the local chapter of the Texas Equal Suffrage Association and affiliated with the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Besides providing publicity work for the league, Baker was also active in the Cloudcroft Baby Sanitarium, an important project of the league. At this time, Baker also worked with the El Paso County Democratic Party in public relations.[2]

In 1918, the El Paso Equal Franchise League became more involved in individual local elections. Baker found herself at odds with other local suffragists because of her support for Claude Hudspeth who was running for Congress. Baker was not the only Hudspeth supporter in the league. He was elected to the U. S. House of Representatives after a contentious election against Zach Cobb. During this campaign, suffrage was a central issue. Both candidates lobbied female voters. Prior to the campaign, Hudspeth had been against women’s suffrage, which is why he was controversial. Some women criticized his past opposition to suffrage and questioned his motives for changing his position. The campaign divided the El Paso Equal Franchise League. In 1990, Baker told the El Paso Times that “Congressman Claude Hudspeth once told me women didn’t have the political minds to vote. . . I hated him for that.” She concluded, “Women have advanced far enough no that if Hudspeth were still living, he’d be horrified.”[3]

Despite her apparent misgivings about him, she supported Hudspeth and campaigned for him in the 1918 Democratic primary. During that election, Baker left the El Paso Equal Franchise League after Mrs. L. T. Kibler stepped down as president of the league because of her support for Hudspeth.[4]

Baker’s political involvement did not stop when women won the right to vote nationally in 1920; she continued her involvement in the El Paso Democratic Party and campaigned for like-minded candidates. Baker headed the women’s campaign organization for the Anti-Ku Klux Klan slate of candidates for the 1922 El Paso school board election, but to no avail: the Pro-Klan candidates prevailed. In 1923, Baker actively campaigned against the local Klan-backed candidate for mayor, P. D. Gardener, who ultimately lost to Richard M. Dudley.

Mildred Baker was a talented writer. She reported on El Paso politics for the local newspapers, wrote two novels, thirty short stories, and sixty feature articles some of which were sold to local and national periodicals. She won various awards for her published work. She was also a member of the local writer’s workshop and active in community theater. She never stopped writing and was working on a novel well into her eighties.

Beyond writing, Baker served as president of the El Paso Pilot Club and the auxiliary of American Legion Post 36. She argued that having political power could change for the better the lives of women and the world around them. “I think men in their hearts still resent taking orders from a woman, but we have people like [Mayor Suzie] Azar and [Texas Gubernatorial Candidate] Ann Richards to teach them better.”[5]

She believed that significant political changes were happening for women. In 1991, elected positions including county judge, major, and a state senator were held by women. She was grateful that she lived long enough to see her work as a suffragist bear fruit. She and other suffragists believed voting would give women the political power to enact significant change. She might have been ridiculed for her ideas and work while she was a suffragist, but when she died she was hailed as a voting pioneer.

Photo Credit: Mary Hamilton Hassen

[1] Donna Weeks, “From Voting to Running to Winning, 105 Years Watches Women Earn Power,” El Paso Times, 25 April 1990, p.24.

[2] “Will Observe Save Babies Week Here,” El Paso Times, 16 February 1916, p. 7

[3] Weeks, [24]

[4] “Equal Franchise League President Resigns Position,” El Paso Morning Times, 21 June 1918, 3.

[5] Weeks, [24]