El Paso Times, Aug. 23, 1925

Birds at Washington Park

By Col. M.L. Crimmins

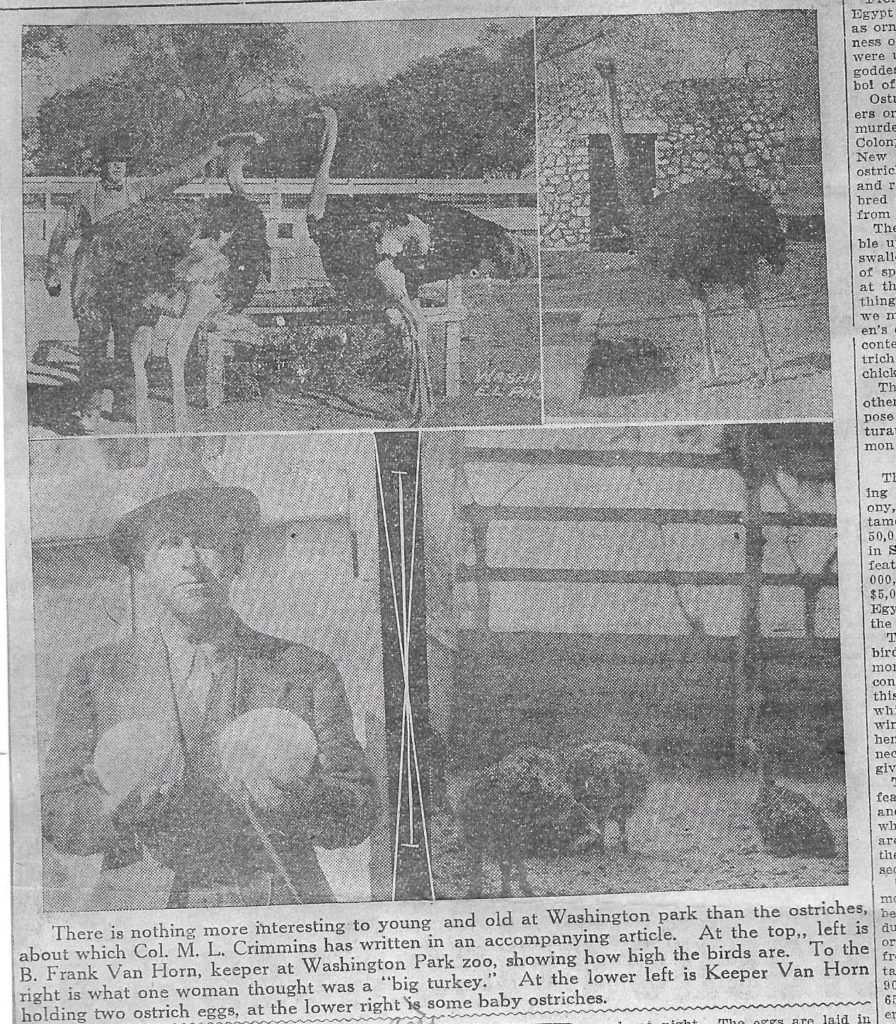

While looking over the animals at Washington Park the other day I spoke to the head keeper, B.F. Van Horn, about the ostriches. He told me these birds were so little known that a very intelligent-looking middle-aged woman came to the enclosure and said, “I never saw such big turkeys before.” This prompts me to tell about ostriches, of which there are two males and two females in the park, just across the canal.

The African ostrich, Struthio camelus, is the largest living bird, and the grown male is eight feet tall to the top of his head and weighs 275 pounds. It was once abundant in most of the open country of Africa except in the Libyan and Sahara deserts. The wings are not used for flight, but they help birds when they run. The ostriches can make 25 miles an hour. The wings are used to sail with, especially when turning. According to the book of Job, “one time when she (a female ostrich) lifted her wings, and ended scorning the horse and his rider.”

Reciprocation

The power of scent is very poorly developed in these birds. They therefore associate with animals whose power of scent is good, such as the zebras and antelopes, which will give them warning of the approach of carnivorous animals that would endanger them, especially at night or when creeping up undercover during the day.

In turn, these birds are able to warn the animals they associate with, during the day, of danger, as they have heads so much higher than any, expect a giraffe, and can see farther. This is especially useful on days when there is no wind or when animals are approaching from the leeward side.

Doesn’t Bury Its Head

From the time of Job, many stories have been associated with the ostrich and its stillness. It has been a subject of many myths. It does become confused when the ostrich was approached by several horsemen from different directions, and it may run in circles. It crouches flat on the ground when it is hiding as animals do, and it extends its neck, but it does not bury its head in the sand, although the body being about 30 inches thick and the neck and head are four inches thick, the body may be the only part that is visible, and some assume that its head and neck are buried.

The eggs of the ostrich are about 20 times the size of a hen’s egg and weigh about three pounds. The hen sits on them during the day and the male at night. The eggs are laid in a hollow, scooped out of the sand.

Plumage of Ostrich

The male bird’s body is covered with the rich black feathers with quills of the wings and tall feathers a pure white, and much prized ostrich plumes. The female is a comber gray, thus nature has provided a protective coloration, the gray of the female blending with the color of the sand makes it hard for them to be seen during the day, and the black of the male makes it hard for him to be seen at night.

Habits of the Birds

They are extremely fond of their young and will attack anything that threatens their safety. Crown wright Schreimer, the well-known African hunter, tells of an old ostrich who charged a railroad train: “As the screeching engine approached, he rushed at it straight from the front, hissing angrily, and kicked. It was cut to pieces the next moment.” The male has been known to sham a broken leg to distract the hunter, from the young, and to kill jackals and other small carnivores in defense of the eggs and the young.

The hens lay about 90 eggs a year. When a dozen are laid they usually start setting.

These birds have a remarkable dance in the spring of the year. Two birds start from opposite ends of the enclosure and begin whirling around until they look like a bur, rising on the tips of their two-toed feet and whirling their wings. When they stop, they are facing each other with mouths open and necks extended in the air.