African American Suffragists in El Paso

By Janine Young

The women’s suffrage campaign in the United States was a remarkable political and social movement that spanned seven decades of American history. A little known aspect of this history is the story of African American suffragists in El Paso. The city had a small yet intensely cohesive African American community that was socially and politically active. Black women from this community formed their own suffrage league, the El Paso Negro Woman’s Civic and Equal Franchise League (NWCEFL), which became the only African American suffrage organization in the United States to apply for membership in the Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA) or the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

Beginning in 1914, El Paso women began organizing for the vote. In 1915, white women in the city formed the El Paso Equal Franchise League (EPEFL). In March 1918, Texas women won partial suffrage when the state legislature passed a primary suffrage bill that gave Texas women their first voting rights by allowing them to vote in primaries. El Paso women immediately began mobilizing to register to vote in the Democratic primary scheduled for July 1918.1

In response to the new law, African American women in El Paso formed the NWCEFL in June 1918 and, with the support of white suffragists in the EPEFL, requested membership in NAWSA. The NWCEFL was one of the few black suffrage organizations in Texas. Its support from the EPEFL is a rare instance of cross-racial cooperation in the suffrage movement in the South. Even though the NWCEFL was denied membership in both NAWSA and TESA, the African American women who were its members continued to advocate for voting rights and to work with local white suffragists in registering and mobilizing women to vote in 1918 and 1919.

Maude Sampson, a 38-year-old teacher at Douglass School and the president of the Phyllis Wheatley Club, led the effort to organize the NWCEFL. On June 12, 1918, Sampson held a planning meeting at her home to create an auxiliary to NAWSA. Fourteen African American women and nine members of the EPEFL were present. According to local newspaper accounts, white members of the EPEFL were present to instruct and assist the black suffragists in organizing a suffrage league and affiliating with NAWSA. That evening, the African American community, both men and women, met at the black Masonic Temple and formed the NWCEFL. The organization was declared to be nonpartisan and primarily organized for the purpose of assisting women to register for the July primary.2

The women who formed the NWCEFL in June 1918 represented the leaders of El Paso’s black community.3 Most were from the middle and professional class although some were working class. Maude Sampson and Emma Coleman was teachers at Douglass School. Sampson and her husband, Edward, were members of the El Paso chapter of the NAACP. Coleman was married to the principal of Douglass School, Professor William Coleman. Callie White was married to LeRoy White, a prominent leader of the NAACP in El Paso and a farmer. Several of the suffragists were married to railroad porters. Lena Kelly was a cook in a private home and her husband, John, had been a Buffalo Soldier, who had fought in the Spanish American War before becoming a porter in civilian life. Toledo Chalmer’s husband, Frank, and Laura Cleveland’s husband, Benjamin, were also porters.

Some of the black suffragists were married to professionals and businessmen. Esther Nixon and Camille Fitzgiles were married to prominent physicians, Dr. Lawrence Nixon and Dr. George K. Fitzgiles. Mary Wells was the wife of Reverend Henry A. Wells, the pastor of AME Church. Annie Shelton’s husband, Christopher, owned a second-hand store in downtown El Paso. Viola Washington was married to Leroy W. Washington, who worked for the U.S. Immigration Service as a guard. Mrs. James Shanklin was married to the first African American mail carrier in El Paso. A few of the suffragists worked as domestics. Julia Nixon worked as a cook after the death of her husband, Charles. Annie J. Berry was a dressmaker and domestic. Georgia Stull worked as a housekeeper and her husband, Samuel, was a barber.

In June 1918, Sampson wrote a letter to Maude Wood Parke of NAWSA requesting membership for the NWCEFL in the national organization. “My dear Mrs. Park [sic], Sampson wrote, “We would like to become an auxiliary branch of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Will you kindly send me the necessary information.” The result was the exchange of several letters between NAWSA in Washington and the leaders of TESA in Galveston. Since membership in the NAWSA was through state suffrage organizations, NAWSA passed the issue to the state association.4

Belle Critchett, president of the EPEFL, wrote to Edith Hinkle League, the Corresponding Secretary of TESA on July 1 in response to an inquiry about Sampson’s request. In her letter, Critchett indicated that white suffragists in El Paso were aware that the black women would apply for membership as an auxiliary of the national association and that one of her members had suggested to the women the idea of writing to NAWSA for instructions. Critchett wrote:

It is not a surprise to me for I knew that Mrs. E. Sampson who is a colored women, President of the Colored Woman’s club here intended to make application as an auxiliary of the National Branch. Twice several members of our League here have been guests of the Colored Women’s club where they have given programs and we have assisted…. I find one has to go slowly here with movements among the colored people. It seems that Mrs. Sampson did not state in her application that she was colored. She is a well-educated woman and is desirous of recognition from the white people.

Critchett finished her letter by assuming, rather naively, that the African American women could become members. “I don’t know what the ruling of the National Association is with reference to colored members. I imagine they are admitted. We want to help the colored people but just now it is rather a hard question.”5

On July 17, 1918, Carrie Chapman Catt, the president of NAWSA wrote to TESA. In a decidedly negative tone, Catt wrote that membership of African American suffrage organizations was up to each state organization but that she assumed that no southern suffrage organization admitted black suffrage associations. Catt suggested that the state organization write to Sampson and request that the African American women in El Paso not “embarrass” the Texas suffrage league by asking for membership.6

On August 31, 1918, Minnie Cunningham, the president of TESA, wrote the official response to Sampson. Cunningham informed Sampson that “the question of the affiliation of organizations of colored women has never come up in Texas, and therefore there is no precedent in the matter. I feel sure you will understand that it is a question which, should it arise, would bring on a great deal of discussion and possibly friction.” Cunningham indicated that the question of admitting African American suffrage organizations into the state association would require the approval of TESA at its next state convention in May 1919. Cunningham deflected the request by stating that she was hopeful that American women would have full suffrage before that time. Cunningham concluded, “You understand that the Texas Equal Suffrage Association is working for full and equal Suffrage for women, – all women, – and have not in our constitution, or, by-laws, or principles, any discrimination against any class.”7

Ultimately, no African American suffrage organization was ever admitted to membership in TESA or NAWSA, and the El Paso chapter’s request was the only one ever received by the state leadership.

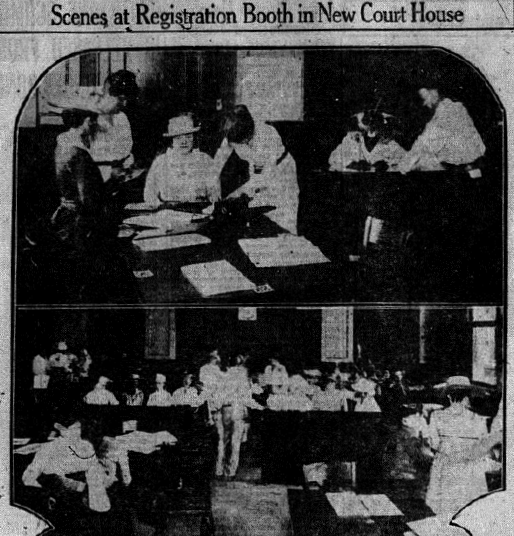

Despite being denied membership in the national organization, the NWCEFL continued its suffrage work. The new primary suffrage law gave Texas women only 17 days to register to vote in the Democratic primary scheduled for July 27. In that time, 386,000 Texas women registered. In El Paso, tax collector Robert Del Richey began to register women on June 26, 1918 at the new county courthouse. By the time the registration period closed on July 12, more than 5,000 El Paso women had registered to vote and more than 4,500 would go on to vote in the primary, including African American women.8

Black and white suffragists in El Paso enthusiastically showed up to register to vote in what the El Paso Morning Times called a “rush of femininity to the new courthouse.” The newspaper reported that “quite a number of negro suffragettes registered the first day” while the El Paso Herald reported that a “number of negresses presented themselves early in the morning.” Only one black woman was not allowed to register after she failed the literacy test. Several African American women were the first to register in their precincts, including Mary J. Ford in Precinct 1, Marie Dickerson in Precinct 4, and Annie Townsend in Precinct 5. Ford and Townsend were members of the NWCEFL.9

The activism of the African American suffragists in El Paso continued through the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920, which gave full suffrage to American women. On May 14, 1919, Texas held a referendum on women’s suffrage that would have amended the state constitution to give women full suffrage. During the referendum, Sampson served as a precinct chairman for three precincts in south El Paso and organized a team of women to telephone voters on the day of the referendum on behalf of the EPEFL.10

In the summer of 1918, a window opened for African American women in Texas. Black suffragists in El Paso took advantage of this opportunity to organize for the vote. The African American suffragists in El Paso, however, were soon forgotten, their names and faces nearly lost to history. In 1930 the League of Women Voters of El Paso held a luncheon to celebrate the 10-year anniversary of women’s suffrage. Although the program included a roll call of members of the EPEFL and recognition of the “men who co-operated” in the suffrage movement, the contribution of El Paso’s black suffragists was not recognized and members of the black community were not invited to attend.11

The celebration of the centennial of women’s suffrage in August 2020 is an opportunity to remedy this wrong and give voice to the African American suffragists who fought for the right of all Americans to vote. The story of El Paso’s black suffragists is a testament to the African American struggle for equality and to the central role that African American women played in the women’s suffrage movement.

Endnotes

- Janet G. Humphrey, “Texas Equal Suffrage Association.” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association, updated July 19, 2017, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/vit01; A. Elizabeth Taylor, “Woman Suffrage,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association, updated June 25, 2019, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/viw01; Judith N. McArthur and Patricia Ellen Cunningham, “Minnie Fisher Cunningham” in Texas Women and the Vote, ed. Jessica Brannon-Wranosky (Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 2019), 26.

- “Wheatley Club Aids Red Cross,” El Paso Herald, May 23, 1918, 4; “Negro Women Voters to Form a Local Society,” El Paso Herald, June 11, 1918, 6; “New Suffrage Club Formed at Masonic Temple,” El Morning Times, June 13, 1918, 10; “Negro Women Form Club for Study of the Ballot,” El Paso Herald, June 13, 1918, 5.

- Information on suffragists in El Paso is from various sources including city directories, published biographies, U.S. census records, birth, marriage and death certificates, burial records, social security records, military records and newspaper articles.

- Maude Sampson to Maude Wood Parke, June 1918, box 5, folder 10, McCallum (Jane Y.) Papers, AR.E.004, 889-1957, Austin History Center, Austin Public Library, Austin Texas; Ruthe Winegarten, Black Texas Women: 150 Years of Trial and Triumph (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1995, 209.

- Belle C. Critchett to Edith Hinkle League, July 1, 1918, box 5, folder 10, McCallum Papers.

- Carrie Chapman Catt to Edith Hinkle League, July 17, 1918, box 5, folder 10, McCallum Papers.

- Minnie Fisher Cunningham to Maude Sampson, August 31, 1918, box 5, folder 10, McCallum Papers.

- Taylor, “Woman Suffrage”; “Suffrage Registrations at Court House Legal,” El Paso Herald, June 11, 1918, 5; “Final Total of Feminine Voters Recorded 5,053,” El Paso Morning Times, July 13, 1918, 5.

- “Women of El Paso Willing and Anxious to Assume Burden of Fuller Citizenship,” El Paso Morning Times, June 28, 1918, 7; “Registration of Women First Day Up to 289,” El Paso Morning Times, June 27, 1918, 12; “Registry of Women is 168,” El Paso Herald, June 26, 1918, 10.

- Lansden, Ollie P. “Lamar Parent-Teachers’ Association is Organized and Officers Elected,” El Paso Herald, May 23, 1919, 8. The May 1919 referendum was defeated by 25,000 votes and Texas women did not win full suffrage until the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in August 1920. White and black women in El Paso also worked together on Red Cross work during the First World War. See, for example, “Line of March for Big Parade,” El Paso Herald, October 1, 1918, 12 and “Red Cross Festival of the Allies,” El Paso Herald, October 2, 1918, 5.

- Handwritten notes for Anniversary League Luncheon at Paso del Norte Hotel, March 26, 1930, box 5, folder 32, Belle Christie Critchett Papers, 1915–1968, MS 386, C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department, The University of Texas at El Paso Library.

Read more about Maud Sampson at

Opinion| PVAMU Alumna Maude Evangeline Craig was social justice in action